Walk 5: Westminster, Lambeth and Tyburn

These three locations are very much related topologically and in the life of Thomas More.

The River Tyburn was a stream (bourn) which ran from the hilly area of Hampstead and Primrose Hill to meet the Thames at four sites. It is mentioned in a charter of AD 959. Its main source was the Shepherd’s Well opposite the north end of Netherhall Gardens, NW3. The river gave the name to the former area of Tyburn, a manor of Marylebone, which was recorded in the Domesday Book (1086); to Tyburn Gallows, where traitors were hanged; to Tyburn Road (present Oxford Street); Tyburn Lane (present Park Lane), and lastly, to Tyburnia (north of Hyde Park). In reaching the Thames, two of the distributors of the River Tyburn formed an island where a small Benedictine monastery was stablished by AD 960. The mouths of those two distributors were approximately at the north bank of Westminster bridge and Lambeth bridge.

That small monastery was dedicated to St Peter, and it was enlarged by St Edward the Confessor in 1065, from then on “this church became known as the ‘west minster’ to distinguish it from St Paul’s Cathedral (the east minster) in the City of London”. As soon as he could, William the Conqueror hurried to Westminster Abbey to be crowned king of England by the Archbishop of Canterbury.

The Shrine of St Edward in the abbey contains the holy remains of the saint and a Catholic Mass is said there yearly on the Saturday nearest to his feast, 13 October. It seems that it could be said at other times by request in advance.

Westminster Hall dates from 1097, soon after the Norman conquest. It became the centre of the administration of the kingdom, the seat of government, the place for the imparting royal justice, and in particular the court of Chancery. From the 15th century the Lord Chancellor had his court there. States trials took place there.

Figure 1: Westminster Hall

In 1352 the Commons began to meet in the Chapter House of Westminster Abbey. In 1512 Henry VIII moved the royal family out of Westminster Palace for the use of Parliament. In 1523, Sir Thomas More made the first known request for freedom of speech in Parliament.

Around Westminster Abbey, Westminster Hall, and Parliament a small village grew, and extended all the way to the City of London. William Caxton had his printing press at Westminster c. 1475.

The Manor of Lambeth was acquired by the archbishop of Canterbury in 1190 for his residence near the seat of government. Lambeth Palace is almost opposite Westminster Palace to which it was linked for centuries by a horse ferry. Other bishops had their own houses around London, always outside the jurisdiction of the City. For instance, before being made archbishop of Canterbury, John Morton, as bishop of Ely, had his London residence in Ely Place.

Figure 2: Riverfront of Lambeth Palace.

Photo in public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=774610

The Tudor gatehouse, in the centre of the picture, was built by Archbishop John Morton in 1486-1495.

After attending St Anthony’s school in the City of London, near his house in Cheapside, Thomas More continued his education in the household of Archbishop John Morton, then Lord Chancellor of England. Thomas More recalls his stay there in Utopia. In this palace, while waiting at tables and learning what a courtier should, Thomas witnessed the ways and dealings of the greatest leaders of England.

Years later Thomas More was summoned to appear at Lambeth on Monday, 13 April 1534, to give his assent to the Act of Succession, in front of Thomas Cranmer (archbishop of Canterbury since 1533), Thomas Cromwell (Secretary of the Council), Sir Thomas Audley (Lord Chancellor after More’s resignation), and William Benson (Abbot of Westminster). After he refused, More was delivered into the custody of the Abbot of Westminster Abbey, and then, on 17 April, he was sent to the Tower of London, entering through the Traitor’s Gate.

In the Library of Lambeth Palace there is a first edition of More’s Utopia.

More’s coat-of-arms can be seen in the Palace of Westminster. More and his father both practised law at Westminster Hall.

Figure 3: Commemorating his work as Speaker of the House is Vivian Forbes’s impressive mural of More Defending the Liberties of the House of Commons in St Stephen’s Hall.

Another mural that adorns a corridor off the Central Lobby represents More and Erasmus visiting the young Prince Henry in Eltham

Figure 4: Thomas More (21) presents a poem to the young Prince Harry (future Henry VIII), on a visit to the Royal Palace of Eltham, in 1499, accompanied by his friend, Lord Mountjoy (21), and Mountjoy’s tutor, Erasmus (33).

More’s famous trial took place on 1 July 1535. A bronze floor-plaque in the middle of the Hall commemorates the event.

Figure 5: Photo Thibault Bastide, 2023.

From Westminster Hall he was escorted to Westminster Stairs. The Constable of the Tower, Sir William Kingston, was in charge of the guard that accompanied the prisoner from there to the Tower. The swift tides made it impossible to pass under London Bridge and instead, the armed party disembarked from the barge at Old Swan Stairs. More was taken onto Old Swan Lane and the turned right along Lower Thames Street and back to the Tower.

The detail of the swift tides so well described by Ackroyd and Reynolds helps us to visualise the difference between More’s first journey to the Tower from Westminster by boat directly to the Traitors’ Gate, and his last journey in which he had to disembark at the Old Swan Stairs and walk ¾ of a mile to enter the Tower on foot. Fortunately, his incident gave Margaret the opportunity to meet her father for the last time. See Walk 2: From Cheapside to the Tower.

Pope Benedict XVI addressed the civil authorities of England in Westminster Hall on 17 September 2010. Among other things he said:

As I speak to you in this historic setting, I think of the countless men and women down the centuries who have played their part in the momentous events that have taken place within these walls and have shaped the lives of many generations of Britons, and others besides. In particular, I recall the figure of Saint Thomas More, the great English scholar and statesman, who is admired by believers and non-believers alike for the integrity with which he followed his conscience, even at the cost of displeasing the sovereign whose “good servant” he was, because he chose to serve God first. The dilemma which faced More in those difficult times, the perennial question of the relationship between what is owed to Caesar and what is owed to God, allows me the opportunity to reflect with you briefly on the proper place of religious belief within the political process.

This country’s Parliamentary tradition owes much to the national instinct for moderation, to the desire to achieve a genuine balance between the legitimate claims of government and the rights of those subject to it. While decisive steps have been taken at several points in your history to place limits on the exercise of power, the nation’s political institutions have been able to evolve with a remarkable degree of stability. In the process, Britain has emerged as a pluralist democracy which places great value on freedom of speech, freedom of political affiliation and respect for the rule of law, with a strong sense of the individual’s rights and duties, and of the equality of all citizens before the law. While couched in different language, Catholic social teaching has much in common with this approach, in its overriding concern to safeguard the unique dignity of every human person, created in the image and likeness of God, and in its emphasis on the duty of civil authority to foster the common good.

And yet the fundamental questions at stake in Thomas More’s trial continue to present themselves in ever-changing terms as new social conditions emerge. Each generation, as it seeks to advance the common good, must ask anew: what are the requirements that governments may reasonably impose upon citizens, and how far do they extend? By appeal to what authority can moral dilemmas be resolved? These questions take us directly to the ethical foundations of civil discourse. If the moral principles underpinning the democratic process are themselves determined by nothing more solid than social consensus, then the fragility of the process becomes all too evident – herein lies the real challenge for democracy

Westminster Cathedral

On Friday, 28 May 1982, at the start of his visit to Great Britain, Pope John Paul II preached in this cathedral. The theme of his visit, which took place around the Feast of Pentecost, was a catechesis on the Seven Sacraments, and in Westminster Cathedral, at his first Mass, he spoken of the Sacrament of Baptism, and at some stage he said:

I would like to recall another aspect of Baptism which is perhaps the most universally familiar. In Baptism we are given a name-we call it our Christian name. In the tradition of the Church it is a saint’s name… Taking such names reminds us again that we are being drawn into the Communion of Saints, and at the same time that great models of Christian living are set before us. London is particularly proud of two outstanding saints, great men also by the world’s standard, contributors to your national heritage, John Fisher and Thomas More.

John Fisher, the Cambridge scholar of Renaissance learning, became Bishop of Rochester. He is an example to all Bishops in his loyalty to the faith and his devoted attention to the people of his diocese, especially the poor and the sick.

Thomas More was a model layman living the Gospel to the full. He was a fine scholar and an ornament to his profession, a loving husband and father, humble in prosperity, courageous in adversity, humorous and godly. Together they served God and their country-Bishop and layman. Together they died, victims of an unhappy age. Today we have the grace, all of us, to proclaim their greatness and to thank God for giving such men to England.

Those visiting Westminster Cathedral will discover that it is a house of prayer, where silence is kept and Mass is celebrated daily.

As it is habitual in big cathedrals, the Tabernacle is kept prominently in the Blessed Sacrament Chapel where we can find people praying all through the day. There is also a Lady Chapel as in most Catholic churches in England, and confessions are also heard all through the day. There is no historical connection between Westminster Cathedral and St Thomas More, but its atmosphere is the atmosphere he would have found in the cathedral of London, Paris or Bruges, or at the church of Nôtre Dame in Antwerp.

In addition to the mosaic of Our Lady in the Lady chapel, an English alabaster statute of the Blessed Virgin Mary dating from 1420 was restored to the Church and enshrined in Westminster Cathedral in 1955. It is now called “Our Lady of Westminster”, and it is situated off the main aisle, under Station XIII of the Stations of the Cross. Interestingly, this English statue, which belongs to the Nottingham school, was spotted at the Paris Exhibition of 1954. Could it be one of the statues of Our Lady that left the country after 1538?

This statue of “Our Lady of Westminster” was used as the model of the new statue of “Our Lady of Pew”, donated by Westminster Cathedral to Westminster Abbey; on 10 May 1971 it was placed in the Pew Chapel in the Abbey, in a niche that had been empty since the Reformation.

Of course, as in many other churches, we find representations of More and Fisher in Westminster Cathedral. They are in the Chapel of St. George and the English Martyrs, half way up on the left.

Figure 6:Altarpiece: Bass relief of St Thomas More and St John Fisher at the foot of the Cross in the Chapel of St George and the English Martyrs in Westminster Cathedral. Photo Mitjans, 2023.

The altarpiece was the last commission of Eric Gill (1882-1940), and the work was completed after his death by his assistant Lawrie Cribb. Eric Gill had designed the Stations of the Cross in the cathedral.

Figure 7: The book held by St Thomas More is inscribed: CAESARI CAESARI ET QUAE SUNT DEI DEO: to Caesar, the things that are Caesar’s; to God, the things that are God’s (Mark 12:17). Photo Mitjans 2023.

Click on link

All the pre-Reformation churches in London were gothic, and those built in the City after the Great Fire are neoclassical. Westminster Cathedral was built in the Byzantine style to distinguish from the gothic and neogothic of the Anglican churches, and the Roman baroque of Brompton Oratory. If the visitor is interested further in church architecture, he will also learn that while all the pre-Reformation churches in England and the Anglican churches built afterwards, are oriented towards the east, this is not the case of Westminster Cathedral, as physical direction was not a matter that concerned the Catholic church builder after the Reformation. The visitor from abroad will learn also why, after the restoration of the hierarchy, we have a Roman Catholic Diocese of Westminster and an Anglican Diocese of London.

Tyburn, 4 May 1535

On 4 May 1535, Sir Thomas More and his eldest daughter, Margaret Roper, standing at the window of his cell in the Bell Tower in the Tower of London, saw the three Carthusians and two other priests being led out of the Tower to die at Tyburn. These were John Loughton, Prior of the London Charterhouse; Robert Laurence, Prior of the Charterhouse of Bevall; Augustine Webster, Prior of the Charterhouse of Axholme; Richard Reynolds, Bridgettine of Syon Abbey; and John Hale, vicar of Isleworth. May 4th is celebrated as the Feast of the English Martyrs.

At his trial, on 1 July, Thomas More was also condemned to death, and he expected to be hanged, drawn, and quartered here at Tyburn.

Today, a bronze plaque in the middle of a busy traffic island marks this infamous place of execution on Edgware Road, at the junction of Bayswater Road, across from and north of Marble Arch.

About two blocks to the west on Bayswater Road is Tyburn Convent where, in the crypt, there is a display of the Tyburn martyrs including a few pictures and a relic of St. Thomas More.

And an engraving on the wall of the convent reads:

Tyburn Tree

The circular stone on the traffic island 300 paces east of this

point marks the site of the ancient gallows known as Tyburn Tree.

It was demolished in 1759

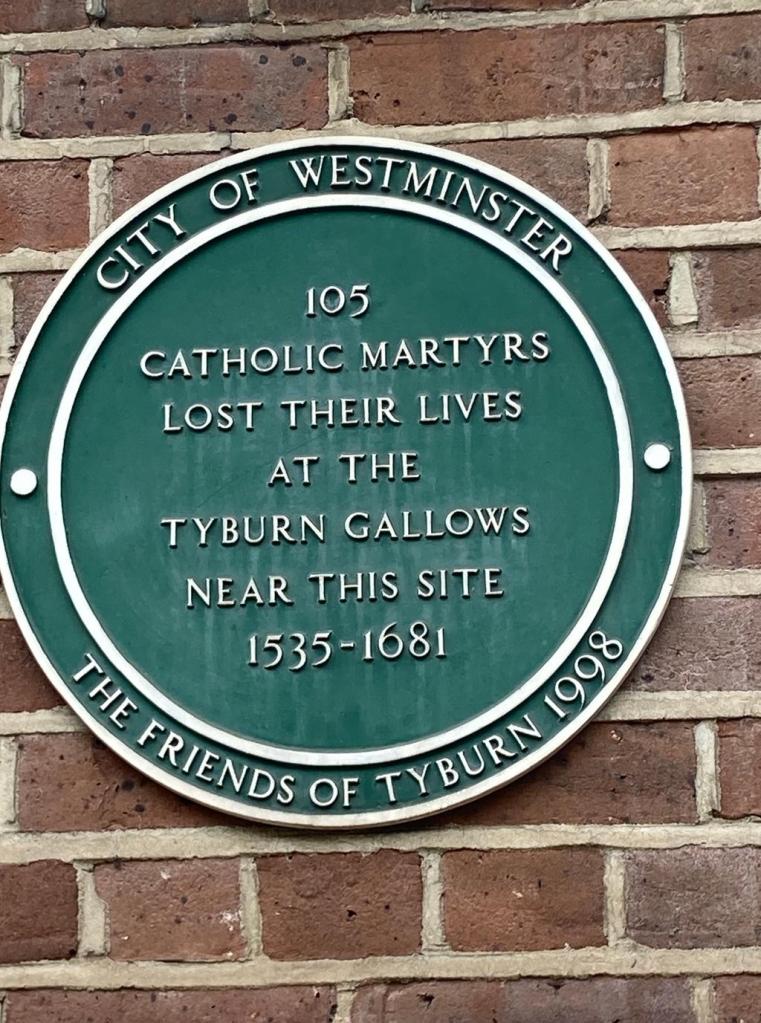

Outside the convent there is a “City of Westminster” plaque placed there in 1998, which reads:

105 Catholic Martyrs

lost their lives

at the Tyburn Gallows

near this site

1535-1681

www.tyburnconvent.org.uk Tyburn Convent, 8 Hyde Park Place,

London W2 2LJ, Tel.: 020 772 37262. A sister is available for guided tours of the Shrine.

Westminster Abbey, Westminster Palace, Westminster Cathedral, and Tyburn Tree are in the City of Westminster, and in Tudor times Lambeth Palace was not more than an isolated Manor surrounded by marshes. So, to complete a general view of the relevance of the present City of Westminster, it is necessary to add Hyde Park, which was bequeathed to Westminster Abbey soon after the Conquest. In 1536 the manor of Hyde was appropriate by Henry VIII who retained it as a hunting ground. The manor of Hyde included Bayard’s Watering, a spring of water, which gave name to the present Bayswater Road. In 1439 Westminster Abbey granted a water supply from this source, the Bayswater Conduit, to the City of London. So, in general terms it can be said that the area now occupied by Hyde Park goes from Tyburn Road (Bayswater Road) on the north, Tyburn Lane (Park Lane) on the east, Kensington on the west. In this setting Pope Benedict XVI gave his Hyde Park Address on 18 September 2010:

The truth that sets us free cannot be kept to ourselves; it calls for testimony, it begs to be heard, and in the end its convincing power comes from itself and not from the human eloquence or arguments in which it may be couched. Not far from here, at Tyburn, great numbers of our brothers and sisters died for the faith; the witness of their fidelity to the end was ever more powerful than the inspired words that so many of them spoke before surrendering everything to the Lord. In our own time, the price to be paid for fidelity to the Gospel is no longer being hanged, drawn and quartered but it often involves being dismissed out of hand, ridiculed or parodied. And yet, the Church cannot withdraw from the task of proclaiming Christ and his Gospel as saving truth, the source of our ultimate happiness as individuals and as the foundation of a just and humane society.

Text and photographs of Walk 5 by Frank Mitjans, 6 July 2023

.