Walk 2: From Cheapside to the Tower

Ironmonger Lane corner with Cheapside

Figure 1: Picture 31: Effigy of St Thomas of Canterbury

Leaving the church of St Lawrence onto Guildhall Yard turn right and then left onto Gresham Street and take the second street on the right, Ironmonger Lane.

On the façade of the building at the end of Ironmonger Lane, corner with Cheapside, there is an effigy of St Thomas, Archbishop of Canterbury, marking the house where he was born.

Figure 2: Ironmonger Lane corner Cheapside

1. William of Normandy conquered England in 1066. The Beckets were Norman immigrants who settled in London; therefore, their son, who became Chancellor of England and Archbishop of Canterbury, was a Norman and a Londoner. He was born on 21 December 1120, then the feast of St Thomas Apostle, and so, he was named Thomas.

Figure 3: Plaque below the effigy of St Thomas of Canterbury

Thomas was educated first in England and later in Paris, where he was known as Thomas of London. Back in England he worked as a clerk for Theobald, Archbishop of Canterbury, who sent him to study law for a year at the University of Bologna. Soon after his return he was ordained deacon in 1154 and made Archdeacon of Canterbury, the highest administrative and legal appointment in the primatial diocese of England. When the young Henry II became king, Theobald advised him to appoint Thomas as his chancellor. Thus, the most promising lawyer of the Church in England, became the most prominent lawyer of the kingdom. At the death of Theobald, in order to control the Church, Henry II put pressure on the elective council of the monks of Canterbury, and on the elective council of the bishops of the ecclesiastical province, and they elected Thomas as Archbishop of Canterbury on 23 May 1162. On 10 August 1162, Thomas received the pallium from the Pope. The pallium was the confirmation of the jurisdiction of Thomas as the Primate of the Church of England. In receiving it, he resigned his post as Lord Chancellor of the kingdom.

Soon there was conflict between the policies of Henry and the rights of the Church. Henry wanted to have the right of election of bishops, control the travelling of bishops overseas, and thus, their communication with the pope, control appeals to the pope, control ecclesiastical courts, and so on. This conflict led Thomas to flee the country, until a peace agreement could be reached and his authority as archbishop of the primatial see recognised. In December 1170, Thomas returned to Canterbury and on 29 December he was murdered in the cathedral by four of the king’s knights. His blood and brains were scattered on the floor of the cathedral, and they were collected by the monks and the people of Canterbury. Many miracles were reported, Thomas was canonized in 1173, he was considered patron of England and in particular the protector of the freedom of the Church all through Europe, and his shrine became a place of pilgrimages together with Rome, the Holy Land, and Santiago de Compostela (The book by Anne Duggan, Thomas Becket, Arnold Publishers, London, 2004, 330 pages, is highly recommendable).

2. In 1227 this site was acquired by the Knights of Saint Thomas to commemorate the birthplace of the saint. The site became the headquarters of the knights (it was called the Hospital of St Thomas Acon – hospital meaning “a house or hostel for the reception and entertainment of pilgrims, and travellers”), and it included a church. So, Thomas More as a schoolboy would have gone daily along Cheapside from his home in Milk Street to St Anthony’s School in Threadneedle Street, passing in front of the birthplace of St Thomas of Canterbury (from Milk Street to Threadneedle Street is a 10 minutes’ walk).

Figure 4: Plaque in Cheapside

3. Thomas More had especial devotion to the saint, and in his last letter before his execution he wrote that he was keen to go to God on the eve of the feast of St Thomas, which was the 7th of July. St Thomas More and St Thomas of Canterbury had similar lives in many respects, both were competent lawyers, were appointed Lord Chancellor by their kings, resigned voluntarily, and died martyrs in defence of the Church.

4. The Mercers’ Guild is the premier livery company of the City of London, first mentioned as a recognised guild in 1304, to protect the exporting of woollen materials, and the importing of luxury fabrics such as silk, linen, and cloth of gold. Originally the guild met near the Hospital, but from the 14th century onwards it held its meetings in rented rooms within the Hospital, and eventually negotiated to purchase part of it. At the beginning of the 16th century the guild built a small chapel (where now there is a corner shop on the ground floor) and the first Mercers’ Hall above it. It is recorded that in September 1509 served there as Latin speaker and mediator between the guild and a delegation from Antwerp led by the chief magistrate of that city.

5. The present headquarters of the Mercers is on the east side of Ironmonger Lane, just before reaching the corner. Notice that on the first floor there is a chapel. Planning regulations required that when the Mercers built the new premises they had to keep the chapel: they moved it from the ground floor to the new location.

Bucklersbury

From the corner of Ironmonger Lane continue on Cheapside towards the east. In arriving to Poultry (at 1 Poultry) turn right onto a covered arcade: Bucklersbury Passage. It is suggested that before leaving the covered shelter the guide has covered everything he wants to say about More’s early years, his meeting Erasmus, his decision to follow the active life of the humanist in service to society, etc.

At the end of Bucklersbury Passage we face the site occupied now by the Bloomberg building. That was the site where he moved when he married Jane Colt in 1505. Her family lived in Nether Hall, Roydon, Essex (See photo 90).

Thomas More’s house in Bucklersbury was leased from the Mercers’ Guild. The period le lived here, aged 27 to 46, is the period when he established himself as a prominent lawyer in the City of London and in Lincoln’s Inn, as well as working for the Mercers and in the Guildhall, as Undersheriff of London. During this period, he went to several embassies to the Continent representing the interests of London first and of the king later, and subsequently he started working at the service of the king after much deliberation, and in 1523 was elected Speaker of the House of Commons.

This is also the period when he built up his family. All his children were born while he lived in Bucklersbury: Margaret (1505), Elizabeth (1506), Cecily (1507) and John (c. 1509).

The well-known household of Thomas More described by Erasmus and all recent biographers, corresponds to the period he lived here. In several of his letters More speaks of his “school”. That included his adopted daughter, Margaret Giggs born c. 1 October 1505, who was probably a niece of More. Erasmus stayed a Bucklersbury, and, at the suggestion of More, the two of them produced the Translations of Lucian in 1506.

More’s wife, Jane, died in 1511, and few months later he married Alice Middleton, widow of John Middleton at St Stephen’s Walbrook. Alice Middleton brought her daughter Alice (1501-1563), into More’s household. And later Anne Cresacre (1511-1577) was made a ward of More, and joined the family.

More mentioned St Stephen’s Walbrook in his Dialogue of 1529. Walbrook was a stream which flowed from the London Wall towards the Thames. It now flows below the surface. At present there is no trace of any connection with Thomas More in the church. The building was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666, and the present building was designed by Sir Christopher Wren.

Figure 5: Church of St Stephen Walbrook in the middle of the picture.

More’s second marriage at St Stephen’s was recorded by John Bouge, who years later, in 1535, after More’s execution, wrote:

as for Sir Thomas More, he was my parishioner at London. I christened him two goodly children. I buried his first wife, and within a month after, he came to me on a Sunday at night late, and there he brought me a dispensation to be married the next Monday without any banns asking; and as I understand, she is yet alive. This Master More was my ghostly1 child; in his confession to be so pure, so clean, with great study, deliberation, and devotion, I never heard many such; a gentleman of great learning, both in law, art, and divinity2, having no man like now alive of3 a layman. Item, a gentleman of great soberness and gravity,4 one chief of the King’s Council. Item, a gentleman of little refection5 and marvelous diet6. He was devout in his divine service, and what more (keep you this privily to yourself) he wore a great hair [shirt] next his skin, insomuch that my mistress7 marveled8 where his shirts was washed. Item, this mistress his wife desired me to counsel to put9 that hard and rough shirt of hair and yet is [it] very long, almost a twelvemonth, ere she knew10 this habergeon11 of hair; it tamed12 his flesh till the blood was seen in his clothes, etc

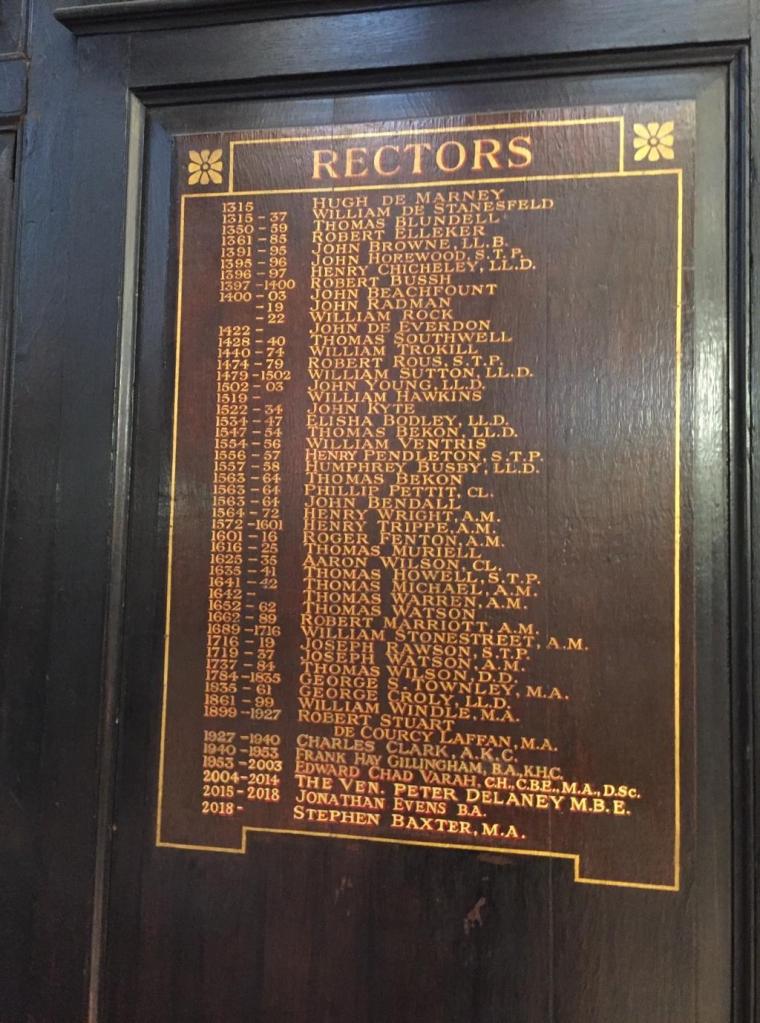

John Bouge’s name, however, does not figure on the present board of rectors of St Stephen’s.

Figure 6: Photo34, list of Rector of St Stephen’s Walbrook

After visiting the church, we continue south along Walbrook. To the right, in the Bloomberg building, we find the entrance to the London Mithraeum. The Temple of Mithras is at level -2. The relevance for our walk is that there is a chronology of London engraved in the walls of the staircase from the ground floor to level -1, which includes a reference to Thomas More.

Figure 7: Photo 35

It is curious, however, that the God everyone worshiped in Utopia is called Mithras (CW4, 217:21): The Utopians, wrote More, “invoke God by no special name except that of Mithras” (CW4, 233:15). Was More aware that his house was built over the Mithraeum? Erasmus has several references to Mithras in his Adagia (CW4, 517); therefore, Mithras was not unknown at the time.

Here finishes our walk in Cheapside.

Walk to the Tower of London

We continue southwards until we reach the Thames embankment, and start on our way to the Tower.

We begin at the Hanseatic Walk. Here the guide could sit or lean on the low wall of the embankment and cover the life of More from his marriage to his imprisonment.

The Hanseatic Walk itself is relevant: This marks the place where ships from the Hansa arrived.

The entry of goods and people from the Continent caused the riots of the Londoners against foreigners which More, as undersheriff of London, managed to control on 1 May 1517.

In the early 1520s, this was the area where Lutheran books were introduced into England. More, as member of the commission against heresy intercepted the distribution of those books.

Figure 8: The photo shows London Bridge. It takes us to 1 July 1535.

More entered the service of the king. In October 1529 he was appointed Lord Chancellor of England. The session of Parliament that started then was very controversial. Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, the previous Lord Chancellor had tried to obtain from the pope an annulment of the marriage of Henry VIII and Queen Catherine, but failed. The king, therefore, resolved that the annulment would be granted in England. During that session of Parliament Thomas More was very active defending the validity of the marriage, while Thomas Cromwell favour the divorce and therefore the submission of the clergy to the authority of the king. By 16 May 1532, the Convocation of Bishops in Parliament, in the absence of John Fisher, bishop of Rochester, agreed that the king was the head of the Church in England, and specifically, that no appeals to the pope on ecclesiastical matters were allowed. The following day Thomas More resigned as Lord Chancellor.

On 13 April 1534, More was asked in Lambeth to give the oath to the Act of Succession, he refused because the Prologue of the Act stated that the marriage of Henry to Catherine was not valid. On 17 April he was taken to the Tower by boat. The various times that he went in and out of the Tower as a prisoner, he did so by boat through the Thames. The last time was on 1 July 1535 when he was taken for trial at Westminster Hall.

Figure 9: Old Swan Pier, where Thomas More disembarked on his way from Westminster Hall to the Tower on 1 July 1535

On his return from Westminster Hall, however, the tide and the weather did not allow the barge to go under London Bridge. They had to disembark at Old Swan Piers and walk on foot to the Tower. By then everyone in London had heard the sentence and they crowed around More. From here we are meant to walk to the Tower along the embankment following More’s footprints.

During this journey of More to the Tower, Meg, his daughter approached him and asked for his blessing.

Figure 10: Meg, daughter of Thomas More, met her father on his return from his trial in Westminster Hall. The picture shows the entrance to the Tower of London through the Middle Tower.

That 1 July 1535 Thomas More entered the Tower of London through the Middle Tower.

That morning and on previous occasions he had gone in and out through Traitors Gate.

Figure 11: Traitors gate from outside the Tower

Figure 12: Traitors Gate from inside the precinct of the Tower of London

Figure 13: Traitors Gate from inside the Tower of London

Figure 14: More was in the Tower from 17 April 1534 to 6 July 1535. His cell is in the octagonal tower to the left of the picture shows a vertical window just above the external wall of the precinct.

Figure 15: The same window from the inside the cell.

During his stay in the Tower, Thomas More wrote the Dialogue of Comfort against Tribulation, A Treatise to receive the Blessed Body of our Lord, sacramentally and virtually, and De tristitia tedio pavore et oratione Christi ante capitionem eius. The original autograph of this last one is kept. It is written in a hurry aware that his end was approaching.

From the Tower More wrote numerous letters; many of these extant letters are addressed to his daughter Meg. The first one was written soon after he was taken in on 17 April 1534, and in it he describes the interrogation at Lambeth to give the oath to the Act of Succession; the last letter is dated 5 July 1535. It is worth reading it inside the cell.

Our Lord bless you good daughter13 and your good husband14 and your little boy and all yours and all my children and all my godchildren and all our friends. Recommend me when you may to my good daughter Cecilye,15 whom I beseech our Lord to comfort, and I send her my blessing and to all her children and pray her to pray for me. I send her an handekercher and God comfort my good son her husband.16 My good daughter Daunce17 hath the picture in parchment that you delivered me from my Lady Coniers; her name is on the back side. Show her that I heartily pray her that you may send it in my name again for a token from me to pray for me.

I like special well Dorothy Coly,18 I pray you be good unto her. I would wit whether this be she that you wrote me of. If not I pray you be good to the other as you may in her affliction and to my good daughter Joan Aleyn19 to give her I pray you some kind answer, for she sued hither to me this day to pray you be good to her.

I cumber you good Margaret much, but I would be sorry, if it should be any longer than tomorrow, for it is Saint Thomas even,20 and the utas21 of Saint Peter and therefore tomorrow long I to go to God, it were a day very meet and convenient for me. I never liked your manner toward me better than when you kissed me last22 for I love when daughterly love and dear charity hath no leisure to look to worldly courtesy.

Fare well my dear child and pray for me, and I shall for you and all your friends that we may merrily meet in heaven. I thank you for your great cost.

I send now unto my good daughter Clement23 her algorism stone and I send her and my good son24 and all hers God’s blessing and mine.

I pray you at time convenient recommend me to my good son John More.25 I liked well his natural fashion. Our Lord bless him and his good wife26 my loving daughter, to whom I pray him be good, as he hath great cause, and that if the land of mine come to his hand, he break not my will concerning his sister Daunce.27 And our Lord bless Thomas and Austen28 and all that they shall have.29

Thomas More.

Figure 16: Bust of St Thomas More in the crypt of St Peter ad vincula inside the Tower of London. Though many people are buried in the Tower, Thomas More is the only who has just a monument in his memory.

Figure 17: On 6 July 1535 More left the Tower of London and walked towards Tower Hill.

Figure 18: Church of All-Hallows by the Tower.

On 6 July 1535 Thomas More left his cell and the precinct of the Tower of London through the gate of the Middle Tower and walked towards Tower Hill. In so doing he would have seen once again the Church of All Hallows, which he knew well. It stands west of the Tower of London. When he reached the spot on the slope of the hill, level with the church, he would have seen the magnificent three-story stained-glass east window of this gothic church. But from then on, walking towards the scaffold, he had the church behind him until he reached the top. Whence he could see the north side of the church where the Lady Chapel stands, and he would probably remember a letter he wrote in 1517 or 1518.

The letter was addressed to his friend Bishop John Fisher. Now the body of John Fisher lay in a ditch grave outside this church after his beheading two weeks previously, on 22 June. Shortly afterwards, he was reburied near the body of St. Thomas More in St. Peter-ad-Vincula. It is worth our while to read most of the letter:

Much against my will did I come to Court (as everyone knows, and as the King himself in joke sometimes likes to reproach me). So far, I keep my place there as precariously as an unaccustomed rider in his saddle. But the King (whose special favour I am far from enjoying) is so courteous and kindly to all that everyone (who is in any way hopeful) finds a ground for imagining that he is in the King’s good graces,

And here comes the reference to the church now in front of him

like the London wives who, as they pray before the image of the Virgin Mother of God which stands near the Tower, gaze upon it so fixedly that they imagine it smiles upon them. But I am not so fortunate as to perceive such signs of favour, nor so despondent to image them.

While he perhaps was recalling the letter, his daughter (tradition tells us) was praying in front of that image of the Mother of God, and She indeed smiled on St. Thomas. (The painting is no longer there, and perhaps there is no need for us to enter the church, but to ponder on More’s recollections. However, in descending from Tower Hill in the direction of the church, we will spot a gothic statue of the Virgin Mary looking after us from the façade of the church above the arch of the entrance porch.)

Figure 19: Place of the scaffolding on Tower Hill

Figure 20: Tower Hill: Record of the execution of St John Fisher on 22 June and St Thomas More on 6 July.

Figure 21: Central plaque on Tower Hill.

Figure 22: Church of All Hallows by the Tower. Tradition has it that after his beheading the body of St John Fisher was deposited in this church, and that perhaps he was buried here. It is most likely that he was buried in St Peter ad vincula with the headless body of St Thomas More. This church is one of the few which were not destroyed by the Great Fire of London; that is why, while most of the City churches are neoclassic, this is Gothic and has a statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary above the main entrance in the north façade.

END OF THE TOWER WALK

- spiritual. ↩︎

- Divinity = theology in early modern English, from Latin; while Theology comes from Greek. ↩︎

- as. ↩︎

- gravity means “influence or authority”, Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 1959, and therefore it makes sense that it is followed by being chief of the King’s Council, thus it would read: Item, a gentleman of great prudence and authority, one chief of the King’s Council. ↩︎

- refreshment. “of little reflection” = he ate little. ↩︎

- Shorter Oxford English Dictionary: Diet means way of living, thus: a gentleman temperate and of a wonderful way of living ↩︎

- Lady Alice, Thomas More’s second wife ↩︎

- wondered. ↩︎

- put off; remove. ↩︎

- ere she knew: before she discovered. ↩︎

- a sleeveless coat of mail. ↩︎

- Old English, tamed = subdued. ↩︎

- Meg, eldest daughter of Thomas More ↩︎

- William Roper ↩︎

- Third daughter of Thomas More ↩︎

- Giles Heron. ↩︎

- Elizabeth, second daughter of More, married to William Daunce ↩︎

- Meg’s maid. While Thomas More was in the Tower, Meg would often send Dorothy there with food and gifts. Dorothy married John Harris, More’s secretary. The couple left England saving More’s papers and letters kept by Meg and Harris, and the two gave their testimonies to Thomas Stapleton who reproduced many of the letters in his biography of More, among others, this same letter. In his biography, Stapleton wrote that “the two Margarets [More’s daughter and Margaret Clement, née Giggs, his adopted daughter] and Dorothy most reverently buried the body” of Thomas More. ↩︎

- Another maid of Meg. ↩︎

- St Thomas of Canterbury was murdered on 29 December 1170. On 7 July the transfer of his body from the original grave to his new shrine in 1220, was celebrated. ↩︎

- Octave of the 29 June. ↩︎

- On 1 July on his way on foot from Old Swan Piers to the Tower. ↩︎

- Margaret, née Giggs. ↩︎

- John Clement. ↩︎

- John More, fourth child of Thomas More. ↩︎

- Anne Cresacre, ward of Thomas More. ↩︎

- Elizabeth, second daughter of More. ↩︎

- Thomas and Austin, the two children of John More and Anne Cresacre born before Thomas More’s execution. Thomas, the grandson of More, was known as Thomas More II. He appears in the two portraits of Thomas More’s Household and His Descendants, now at the National Portrait Gallery and the Victoria & Albert Museum. ↩︎

- Thomas More often praised large families. John More and Anne Cresacre got eight children. ↩︎