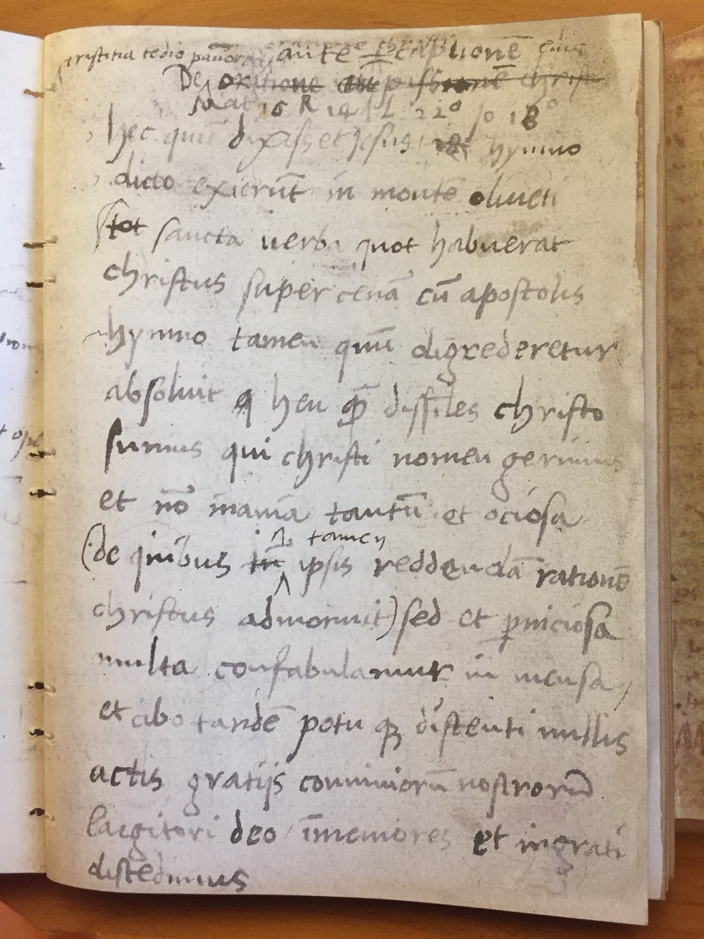

Manuscript of De tristitia tedio pavore et oratione christi

The “Discovery” of the Autograph of Thomas More’s De Tristitia Christi through Andrés Vázquez de Prada, June 2021

Moreana, Volume 58 Issue 1, Page 112-124, ISSN 0047-8105, June 2021.

To download the full text, click here: https://www.euppublishing.com/doi/full/10.3366/more.2021.0094

Full Text

The recently published Essential Works of Thomas More edited by Gerard B. Wegemer and Stephen W. Smith (Yale University Press, 2020), which includes most of the works by Thomas More and the earliest biographical accounts, gives the opportunity of revising assumptions and of giving credit where credit is due. In the Introduction to “The Sadness, the Weariness, the Fear, and the Prayer of Christ before He Was Taken Prisoner,” the editors write that “the original manuscript, in More’s own hand, was rediscovered in 1963” in Valencia. This is an invitation to a more detailed account of how that happened, and I gladly take up the challenge in order to discharge an overdue debt.

Andrés Vázquez de Prada (1924–2005) was born in Valladolid, Spain, studied at the Universities of Valladolid and Seville, and, soon after gaining his doctorate on Political Law from the University of Madrid and lecturing on “Political Law and Philosophy of Law” at the University of Seville, he moved to London as attaché of the Spanish Embassy (1951–1990). During his stay in England, in 1962, he published his biography, Sir Tomás Moro: Lord Canciller de Inglaterra, Ediciones Rialp, Madrid, 395 pages in hardback, which has been republished in a total of eight editions.

The first edition included three Appendices. The first dealt with the Epitaph in Chelsea Old Church, near where the house of Thomas More stood, a place visited by Vázquez de Prada as he wrote in the Prologue of the book. Appendix II gave a contemporary Spanish account of the trial and execution of Thomas More; and Appendix III tried to identify the sitter of a painting as Thomas More.

The second and third editions of 1966 and 1975 respectively brought a new appendix, Appendix IV, entitled “The Manuscript of the Passion of the Lord.” There Vázquez de Prada explained that a reader of the first edition—this was in fact Professor Francesc Carreres de Calatayud (1916–1989), Director of the British Institute in Valencia—had been surprised that he had not mentioned the Valencia manuscript which was well known locally and kept in the Real Colegio Seminario de Corpus Christi in that city, also called del Patriarca. Vázquez de Prada contacted the College and was able to get hold of a microfilm of the whole of it. He asked the opinion of professor Geoffey Bullough of King’s College London.1 The two of them, after comparing it with other autographs of More, were able to confirm its authenticity. The news was joyfully received by Germain Marc’hadour and by “friends from Yale University.” Vázquez de Prada emphasized that of course it had not been a new discovery as it was well known at Corpus Christi College, and he thanked the members of the College and Professor Carreres de Calatayud. We must credit Vázquez de Prada, however, with having been instrumental in making international scholars aware of the existence and authenticity of the manuscript, the only extant long work in the very hand of Thomas More.

What in Appendix IV is entitled “The Manuscript of the Passion the Lord” is the text that in the Opera Omnia is called “Expositio Passionis Domini, ex contextu IV. Evangelistarum, usque ad comprehensum Christum: Authore Thoma Moro, dum in arce Londinensi in carcere agebat. De Tristitia, Taedio, Pavore, Oratione Christi ante captionem ejus;” and in the English Works appears as “An exposicion [sic] of a parte of the passion of our savior Iesus Christi, made by syr Thomas More knight (whyle he was prisoner in the tower of London) and translated into englyshe, by maystres Marye Basset, one of the gentlewomen of the queenes maisties privie chaumber, and nece of the sayde syr Thomas More.” This text was commonly known as the Expositio Passionis or just the Expositio. The manuscript starts with the words “De tristitia tedio pavore et oratione christi ante captionem eius,” which fill the full first line of folio 1. The Yale Edition called it “De Tristitia Christi.” At times this text has been considered part of “A treatise upon the passion of Chryste (unfinished) …,” included in English Works; but that is not the case. Indeed, the Treatise on the Passion was left unfinished when More was taken prisoner, and probably by the time he wrote about it in his letter to John Harris, his secretary, from Willesden on Easter Sunday, April 5, 1534. While De Tristitia covers what More wrote in the second line of folio 1: “Matthew 26, Mark 14, Luke 22, and John 18;” and finishes “ante captionem” as Moro wrote in the first line.

When Andrés—in order not to keep repeating his long surname I will instead use his first name—left England in 1990 he handed over to me his collection of books on Thomas More. Inside the De Tristitia Christi, volume 14 of The Yale Edition of the Complete Works of St Thomas More, I found a number of pieces of paper. The most interesting is a typed letter to Andrés signed by Professor Geoffrey Bullough, from King’s College, London, and dated 30.11.63. It reads:–

Dear Mr. de Prada,

I am sorry not to have replied before, but I had to go through most of the More MS. to be sure what was in it, and now I have had to modify my first impression somewhat as far as the last few pages are concerned; and I have had no time to follow up the note on the provenance of the MS. Preparations for my visit to India occupy me much, but I am hoping to write a short article this week before I leave England. I have heard from Yale and have advised them to get permission from Valencia to use the MS., and have promised the editors every help I can give in their editorial work. No doubt you could help them too! Below is a note summarizing my conclusions so far. You will want to give of it in your new edition of the Life. Please do so; and if I can add anything this week, please ring me up.

‘A holograph manuscript which has been in the College of Corpus Christi in Valencia has recently been examined by Professor G. Bullough of the University of London and found to consist of the Latin portion of the unfinished treatise on the Passiontogether with notes and drafts for the short piece, Quod pro Fide fugienda mors non est, and for the Precatio ex Psalmis Collecta, both of which follow the Latin Passion in early editions of More’s Latin Opera.

Almost the only surviving holograph manuscript of a major work by More, the MS. has special value because, being heavily corrected, it throws valuable light on his method of composition. Apparently, he made preliminary notes and wrote out suitable quotations in rough, then composed rapidly in Latin, so rapidly that at times he would write a word twice, then correct it, or revise a phrase before finishing his sentence. Later he would go over the whole section, cross out passages with which he was dissatisfied, and insert improvements or afterthoughts.

The revised text corresponds closely with that in the 1565 and 1566 editions of the Opera, whose editor declared that the Passion was unfinished because when More had got so far, “omni negato scribendi instrumento, multo urius quam antea in carcere detentus.” This would probably be after his second examination on 3 June, 1535. The MS. shows some revision of the last section “De Christi Captione,” which ends at the bottom of a page, without any sign of sudden interruption.

Whether More himself made a fair copy of the Passion we do not know. The books which he had in prison were taken away from him at this time. Later his daughter Margaret Roper was accused of cherishing her father’s head as a relic and of retaining some of his books and writings. She replied that “she had hardly any books and papers but what had already been published, except a very few personal letters” (Stapleton). The word “hardly” may be significant. Maybe Margaret had the 170 or so leaves which at some time were bound up in green velvet, making a volume of about octavo size. After her death in 1544 it may have passed to William Rastell, who collected all of More’s writings that he could, and was responsible for the publication of the English Works in 1557.

The later history of the MS. is described in the book itself, for it contains a note in the handwriting of St Juan de Ribera, founder of the College of Corpus Christi:

(You have this inscription already)2

How Pedro de Soto, Confessor of the Emperor Charles V obtained the MS. is a matter for further inquiry. Was it through Eustace Chapuys, Imperial Ambassador in England during More’s last days? Or did he obtain it later, when in England between 1553 and 1558 as a preacher and teacher at Oxford, perhaps through Cardinal Pole or from one of More’s family? From him it passed to the Duke of Alva, and from him to one of his family, the Conde de Oropesa (a son?), who gave it to St Juan de Ribera (a great collector of manuscripts, as the College library still shows).’

If you have any more ideas about the history of the MS. in Spain I should be grateful for them. Which Oropesa was it?

Yours sincerely, G. Bullough

The second piece of paper is a cutting from The Tablet of December 21st, 1963, page 1379, which contains the article by Geoffrey Bullough, “MORE IN VALENCIA: A Holograph Manuscript of the Latin ‘Passion’,” which expands the draft of the letter of 30 November.

The next one is a typed rough paper—Item 3—written by Andrés, which contains a draft of an article sent by him to Germain Marc’hadour. Subsequently Marc’hadour himself signed the article and it was published in Moreana, no. 2 (February 1964), pp. 106–108. It starts: “This is startling news, so startling that many a doubting Thomas will need confirmation of Mr Bullough’s evidence, before admitting that here is More’s own hand.” Within the article Marc’hadour added, “The cutting from THE TABLET—[…]—was kindly sent me by Professor Andrés Vázquez de Prada, who is all the more interested in the discovery as he is preparing a second edition of his Sir Tomás Moro.” This piece was included in the journal among other reviews signed by Marc’hadour of various recent publications such as The Likeness of Thomas More by Stanley Morison and The Trial of Saint Thomas More by E.E. Reynolds.

Marc’hadour continued on the topic, and in Moreana, no. 9 (February 1966), pp. 93–96, wrote the first part of an article entitled “Au Pays de J. L. Vives: La plus noble relique de Thomas More,” in which he refers to Andrés: “J’avais déjà fait ces constatations sur le microfilm dont M. de Prada m’avait fait cadeau à Londres en juillet 1964.” The second part of that article appeared in the following number of the journal (Moreana, no. 10, May 1966, pp. 85–86). There it is already advanced that Clarence Miller was preparing the edition of De Tristitia Christi for the Yale Complete Works.

The next stage of this story was indeed the addition of Appendix IV for the second edition of Andrés’s book in 1966, pp. 526–529, in which he explains the finding, and refers to his dealing with Geoffrey Bullough and Germain Marc’hadour, citing the articles in The Tablet and in Moreana. He also mentions the awaited Yale Edition of De Tristitia Christi being prepared by Clarence Miller. Appendix IV appeared also in the third edition of Andrés’s book printed in 1975, and the fourth edition of 1985.

The Yale Edition of De Tristitia appeared in 1976 in two parts. Part I includes the facsimile of the Valencia manuscript folio by folio on even pages, and the transcription of the Latin text and the English translation on the opposite odd pages: it is an impressive edition. Part II includes Introduction, Commentary, Appendices, and Index. In the Introduction Miller wrote that the manuscript “was brought to the attention of the English-speaking world by Geoffrey Bullough in 1963” and gives the reference to the article in The Tablet of December 21, 1963 (CW 14, part II, p. 697 and footnote), but there is no mention of Andrés’s role even though it was he who had informed Bullough of the existence of the manuscript.

Sir Tomás Moro: Lord Canciller de Inglaterra continues to be read and, as said, there have been eight editions by Rialp.3 Since the publication of the Yale Edition of De Tristitia Christi in 1976, however, Andrés considered it unnecessary to include the full story of the finding of the manuscript, and therefore, from the 5th edition of 1989, Appendix IV has been omitted; instead, the information about the finding of the MS. is included briefly in footnote 26 of Chapter XV where mention is made of the role played by Carreres de Calatayud, and of the deep study made by C. H. Miller for the critical edition published by Yale University Press.

SIR TOMÁS MORO BY ANDRÉS VÁZQUEZ DE PRADA

So far, I have only mentioned the lack of acknowledgment of Andrés’s finding by the international community; but, of course, the reader may like to know about Andres’s book and its relevance to the knowledge of Thomas More by the Spanish readership. Andrés wrote a full biography of More based on all the scholarly sources available at the time. In the Prologue he stated that he had tried to write a fresh profile of More guided by his mind, even though it is not surprising that “the imperious voice of the heart bursts forth like a howl of the soul through the pages of his book.”4 Indeed, Andres’s admiration for More, and for More’s human and spiritual worth is made evident.

Like most authors he started by referring to the earliest biographies of More which he qualified. The familiar prose of Roper; the excellent style of Harpsfield; the precise small fragments of Rastell; the great and most important biography by Stapleton; that of Ro.Ba. based on Stapleton and Harpsfield; and the family traditions transmitted by Cresacre More. In addition to all the works of More and the correspondence of Erasmus, Andrés made use mainly of the Chronicle of the reign of Henry VIII by Edward Hall, 1542, the Calendar of Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, of the Reign of Henry VIII, and the State Papers of the same period; but he also researched the very relevant material found in the general Archive of Simancas, Spain, and the Calendar of Letters, Despatches and State Papers, relating to the negotiations between England and Spain, 1485–1558. For instance, interestingly, Andrés reports that to the consultation of Henry to various universities about his marriage with Catherine, Charles V responded with studies by Italian and Spanish universities; in particular, the judgement of the Spanish theologian Francisco de Vitoria, De matrimonio inter Regem et Reginam Anglorum, January 25, 1531. Vitoria (1492–1546) is the founder of the School of Salamanca and, in his Relectio de Indis, a defender of the human rights of the American Indians, and creator of the studies of international law: a man of great influence in the Theology of the sixteenth century; but he does not appear in the index of biographies of More such as those by Ackroyd or Marius. This shows that some recent biographies of More in English lack a wider vision. In this context, however, it must be acknowledged that Vitoria is indeed cited in the volume on Utopia of The Complete Works of St Thomas More, ed. Edward Surtz, S.J. and J. H. Hexter; in Brian Gogan, The Common Corps of Christendom; and in the biography of Henry VIII by J. J. Scarisbrick (1968).

From the very beginning Andrés emphasized throughout the book that More was always aware of the afterlife. In the fusion between More’s human qualities and temperament with his Christian understanding of the world there is a constant link between earthly joy and the presence of death, so much so that when climbing to the scaffold at the end of his life he would improvise humorous sentences with the same audacity and charm as when he took the initiative in taking part on the stage as a child in Lambeth Palace. For Andrés the thread that unifies all of More’s life is his vocation to love God as a layman through his work as a lawyer and through marriage. This is a decision More took early on considering his own personal knowledge of the London Charterhouse, and having studied St Augustine’s City of God and the Life of Pico.

In discussing Utopia, Andrés made use of the great appreciation of work by the Utopians in order to speak of sanctification of work. This was More’s hidden life: daily work. For Andrés the whole of Utopiais autobiographical. Andrés defines the spiritual vocation of More in two concepts, immersed in the world and fully dedicated to God. The Utopians unite the contemplative and the active life. Another aspect in Utopia emphasized by Andrés is their belief in the afterlife. For the Utopians the painful transition of death is the beginning of a joyful life: “happiness after death will be beyond measure.” Continuing analyzing their beliefs, Andrés gave the following quotation: “There are two schools of thought5 among the Utopians. The one is composed of celibates. … The other is just as fond of hard labor but regards matrimony as preferable, not despising the comfort which it brings and thinking that their duty to nature requires them to perform the marital act and their duty to the country to beget children.” Here Andrés saw More’s vocation to marriage as one of the ways to respond to a full Christian calling, as explained also by Cresacre More.

Andrés continued emphasizing that More opted for seeking holiness through participation in politics, trying to Christianize society, being in the world but not being worldly. Andrés, in commenting on a conversation between More and Henry VIII reported by Roper, wrote that More avoided confusing the spheres of politics and religion, though they are related in society and in the individual conscience of each one. More, for Andrés, practiced Christian tolerance respecting the opinions of others, and holy intransigence, not giving way where the law of God does not allow it, such as in the case of the validity of Henry’s marriage and his claim of supremacy over the Church in England. Through all his book More appears as a man of integrity, and a man of prayer. Also, as a man who trusted in prayer for specific intentions, whether Meg’s health or Roper’s faith.

The biography goes on to discuss More’s three desires: Peace among the Christian princes, unity in Christ’s Church, and the solution of the King’s matter. The insights of Andrés once More was in the Tower are relevant. In conversation with Meg, Thomas More saw himself as fortunate because God treated him as a child:

God has made me a spoiled child, and placed me on his lap and dandles me.6

The awareness of his divine filiation was a characteristic of More’s spiritual life, the source of his trust in God, and thus of his peace and serenity; and he writes to Meg, “my heart hop for joy.”7

Andrés also mentioned the close friendship of More towards John Fisher in the Tower. During Christmas 1534, for the feast of St John Evangelist, on 27 December, More sent Fisher apples and oranges, together with a picture of St John; and, on New Year’s Day he sent him a scrap of paper on which, jokingly, More had written, “£2,000 in gold,” and a picture of the Epiphany. The account of the last months of More in the Tower are especially moving. For the description of the trial, Andrés follows the Spanish Account, kept in the Archive of Simancas, which he considers the most trustworthy and might be based on the letters from Chapuys, the Spanish Ambassador, as reported by Erasmus.

Reading Andrés’s Sir Tomas More, the overall impression is that More focuses on heaven, death as the way to heaven, and the Passion of Our Lord which has opened the gates of heaven. It is difficult at times for the reader of More to get these three realities together. Neither death nor the Passion of Our Lord have any negative connotations for More. Death is the joyful entering into heaven; the Passion of Our Lord the manifestation of the love of Christ for man; heaven, the child’s union with his Father God. Of course, for More heaven requires faithfulness to God; but in the same discourse where More states that faithfulness is required he avoids judging those who evidently are not faithful and prays for them to join him in heaven.

SIR TOMÁS MORO WITHIN THE SPANISH WORKS ON THOMAS MORE

At this stage the reader of Moreana may well be interested to hear about the knowledge of More in Spain before Andrés’s publication, and his subsequent influence. The first of these two aspects is answered in the Introduction of Andres’s book. In 1588 Pedro Rivadeneyra wrote the Historia eclesiástica del cisma del reino de Inglaterra in which More was not mentioned, but in the 1595 edition Rivadeneyra added a full chapter on Thomas More based on the biography of More published by Thomas Stapleton in 1588 (see my review of the English translation of the Historia by Rivadeneyra in Moreana, no. 55, June 2018). In the same sixteenth century, More appears also in the anonymous Chronica del Rey enrico octavo de Inglaterra (sic). Years later Fernando de Herrera wrote a number of moral meditations and anecdotes of the saint entitled simply Tomás Moro (1617). Francisco de Quevedo, one of the most prominent poets and writers of the Spanish Golden Age, wrote a piece on More as the Prologue to the first Spanish edition of Utopia (1637). Little else was published in Spanish until Lucrecia Saenz Quesada penned Sir Thomas More, Humanista y Mártir, in 1934; but she addressed Argentinian readers, her biography of More was published in Buenos Aires, and was little known in Spain. The Spanish translation of the biography by R. W. Chambers was also published in Argentina in 1946.

Although the biography by Ernest Edward Reynolds was translated into Spanish and published by Rialp in 1959 under the title Santo Tomás Moro, within the collection Patmos: Libros de Espiritualidad, no. 94, it seems accurate to say that from 1962, for more than forty years the book by Vázquez de Prada was the main source on Thomas More for the readers of Rialp and for most Spaniards as there were almost no other books on More available whether originally in Spanish or in translation, apart from the translation of Thomas More et la Crise de la Pensée Européenne by the theologian André Prévost published by Ediciones Palabra, Madrid, 1972, which is much more a history of ideas than a biography. Later on, however, a number of biographies of More were translated and published in Spain such as those by the German Peter Berglar in 1993, Peter Ackroyd in 1998, Gerard Wegemer in 2003, the French Bouyer in 2009, and my own translation of James McConica’s in 2016. The seventh edition of the biography by Andrés was published in 2004, presumably because there was demand for it. It seems to me therefore that from 1962 to 2004 Andrés’s book has been the best-selling biography of More in Spain.

***

Returning to the manuscript of De Tristitia, it is fair to say that Andrés’s finding did not alter the text of his book. There he cites De Tristitia from the Latin text in the 1565 Opera Omnia and from the translation by Mary Basset given in the 1557 English Works. These were the two sources used by everyone else. In the Opera and in the English Works the work is entitled Expositio Passionis Domini. And the text and Basset’s translation do not differ much from the Valencia holograph. Here the praise is due to Clarence Miller (1931–2019) for his in-depth study of all aspects of Thomas More’s last work which is published as the 500-page Part II of volume 14 of the Yale Edition of the Complete Works of St Thomas More, which, of course is not going to be summarized here, but it is worth emphasizing that under the heading of “Habits of Composition” and “Visions and Revisions: Patterns of Style and Thought” (CW 4, 745–776), Miller tells us much of the character of More. Miller considers also “The Transmission of the Manuscript” (CW 4, 716–724) from the Tower to Corpus Christi College in Valencia and here there is nothing to be added to his explanation.

ANDRÉS VÁZQUEZ DE PRADA’S WRITINGS

The editor of Moreana suggested giving an overall view of Andrés as an author. As said he worked in London from 1951 to 1990. During that time he wrote a number of articles related to literature, politics, and religion such as “Amistad y Política,” “Dramatización de la Teología,” “Don Quijote, caballero político,” “Religión y Política,” “La fama eterna,” and so on. He translated two books into Spanish: Newman’s Dream of Gerontius—El sueño de un anciano (Rialp 1954)—and Utopia (Rialp, 1989). His first original books are Estudio sobre la Amistad (Rialp, 1956 and 1975), Sir Tomás Moro (Rialp, 1962), and El sentido del humor (Alianza, 1976).

In 1983 Andrés produced a biography of Josemaría Escrivá (1902–1975), El Fundador del Opus Dei. This was based on published material easily available. In 1990 Andrés, however, moved to Rome and there he researched for an authoritative biography of Escrivá based on unpublished material, which he wrote and was published in three volumes, completing more than 2,000 pages. The first volume appeared in 1997 and the third in 2003, after the canonization of St Josemaría Escrivá which took place in Rome on October 6, 2002. The question, therefore arises, of the relationship between St Josemaría and Andrés’s book on St Thomas More, and the possible mutual influence. Two facts are relevant: St Josemaría had named St Thomas More as intercessor of Opus Dei in 1954, together with St Nicholas of Bari, St Jean Marie Vianney, and St Pius X; and he spent some months in London during the summers of five years 1958–1962.

In Sir Tomás Moro, Andrés mentioned St Josemaría without naming him. He said that, after he visited a number of places related to More, read his works and researched his life, he decided to write about the gigantic spirit of that man, and that one day, going to St Dunstan in Canterbury [where the head of St Thomas More is buried] a “fatherly and friendly voice” encouraged him to complete a book (Sir Tomás Moro, Prologue, First edition, 1962, p. 8). As far as Andrés could recall when he wrote about the matter on 4 September 1975, within his memories of St Josemaría who had died on 26 June that year, that conversation took place on August 10, 1959. In those memories of 1975, Andrés said that he had been researching on More since the previous year after noting St Josemaría’s recourse to St Thomas More, and that he had planned to write some articles on More. St Josemaría, in encouraging him to go ahead with a full biography went on to discuss the need to enter into the psychology of his subject, to study in depth the development of his ideas, and to contextualise. The conversation turned to the work expected of a historian, and St Josemaría insisted on the need to be objective in collecting data truthfully.8 From autumn 1959 to spring 1960, Andrés had the opportunity of working on his book in Spain; presumably it was then that he researched the material available in the Archive of Simancas, in the Spanish National Library and the Royal Academy of History. Later on, in the Prologue to his first book on El Fundador del Opus Dei (1983, p. 13), Andrés recalls that St Josemaría encouraged him, in writing about More, “to enter inside the man.” In summary, St Josemaría’s recourse to St Thomas More was prior to Andrés book, which was undertaken with his encouragement. I think that it would be very interesting to write about the affinities between the teaching of St Josemaría, and the life and works of St Thomas More, but this is a theme beyond the scope of this article which aims only to focus on the role of Andrés in spreading the knowledge of the Valencia manuscript.

***

To finish the topic of this investigation, it is worth mentioning that the Corporation of the City of Valencia published in 1998 an excellently cared-for edition of De Tristitia Christi, which includes a real-sized facsimile of the manuscript properly bound together with a 17 cm × 24 cm volume which contains 60 introductory pages, and 178 pages that correspond to each folio of the manuscript; each of these pages includes the Latin transcript from the folio and its translation into Spanish. The transcript, translation, prologue to the translation, and notes have been compiled by Francisco Calero; the Introduction by Angel Gómez-Hortigüela.

The Introduction includes a brief biographical profile of Thomas More, his friendship with the Valencian scholar Juan Luis Vives, his imprisonment and the writing of De Tristitia Christi, and finally how the manuscript—A Hidden Treasure—reached Valencia and came to the attention of the English-speaking world. Ángel Gómez Hortigüela ends his account as follows.

In December 1963, Andrés Vázquez de Prada, biographer of Thomas More, showed the microfilm of the manuscript to Professor Geoffrey Bullough, of King’s College, London. Comparing it with other manuscripts of More, they confirmed its authenticity and publicized their “discovery” among the Anglo-Saxon scholar community who had hitherto been unaware of its existence.

Other specialists in More, Germain Marc’hadour, and various scholars of the University of Yale, corroborated the authenticity of the authorship, in particular by comparing the handwriting with the jottings on the Book of Hours used by Sir Thomas. From then on, they started to work intensely on his last book, “the most noble relic of More,” the legacy of a just man. The culmination of this work is the critical edition, together with the English translation, and extensive commentaries, carried out by the extraordinary effort of Professor Clarence H. Miller.

Notes

1 It is likely that Vázquez de Prada was introduced to Bullough by a common friend, Professor Alexander A Parker, Cervantes Professor of Spanish at King’s College London.

2 This phrase is found in parenthesis in the letter from Bullough to Andrés. The inscription by the hand of St Juan de Ribera reads:

Thesaurus absconditus

este libro me Embio El conde de oropesa, diziendo [sic] que era del Señor don

Fernando de Toledo, al qual selo dio El padre frei pedro de Soto confessor del

emperador rei i Señor carlos .V. porque era de thomas moro y escrito de su mano

That is, “The Count of Oropesa sent me this book, for it had been written by the hand of Thomas More, saying that it belonged to Sir Fernando de Toledo, who received it from Fray Pedro de Soto, confessor of the Emperor, King Charles V.”

3 Just to complete the information on the various editions by Rialp that have been checked:

First edition, 1962, hardback, within the collection Forjadores de Historia, Prologue, fourteen images, footnotes, and appendices I–III, 395 pages.

Second edition, 1966, hardback, within the collection Forjadores de Historia, Prologue, fourteen images, footnotes, and appendices I–IV, 400 pages.

Third edition, 1975, paperback, within the collection Patmos: Libros de Espiritualidad, no. 157, Prologue, Note to the third edition, footnotes, and appendices I–IV, no images, 555 pages.

Fourth edition, 1985, as per the third edition.

Fifth edition, 1989, hardback, within the collection Forjadores de Historia, Prologue, Notes to the third and fifth editions, appendices I–III, and endnotes instead of footnotes, no images, 353 pages. De tristitia Christi, ed. C. H. Miller, 1976, is included in the Bibliography. This edition has at least an editorial inaccuracy: note 26 of Chapter XV makes reference to Appendix IV, but Appendix IV had already been omitted.

Sixth edition, 1999, hardback, omits reference to the collection Forjadores de Historia, and omits notes to previous editions. A new paragraph at the end of the Prologue has been added including information on the statute of St Thomas More in Chelsea which before was part of the Note to the third edition. Reverts to having footnotes; eight images; appendices I–III, 430 pages. The bibliography includes more recent biographies by Gerard B. Wegemer (1995) and Peter Ackroyd (1998). The sixth seems to be the definite edition. It is the edition referred to in this article.

Seventh edition, 2004, as per the sixth edition.

Eighth edition, 2010, published posthumously, identical to the sixth edition except for the cover which includes a portrait by the school of Hans Holbein from the Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

4 Sir Tomás Moro, 6th edition, 1999, p. 14.

5 The original has “haereses” (used by Cicero), which is often translated as “schools of thought.” In CW 4, 226, it is translated by “school.” Others translate it as “sect.” It seems to me that the later is not accurate because More uses the Latin “secta” for “sect,” for instance in CW 5.I, 690, 6 (Latin) and 691, 7 (English).

6 For me thinckethe god makethe me a wanton, and settethe me on his lappe and dandlethe me (Roper, Life of Sir Thomas Moore, Early English Text Society, 1935, 76, 16–18).

7 Correspondence, Letter 210, 26.

8 Cf. Andrew Hegarty, “St Thomas More as Intercessor of Opus Dei,” Studia et Documenta, Rivista dell’Instituto Storico San Josemaría Escrivá, Rome, vol. 8, 2014, pp. 91–124, in particular p. 117