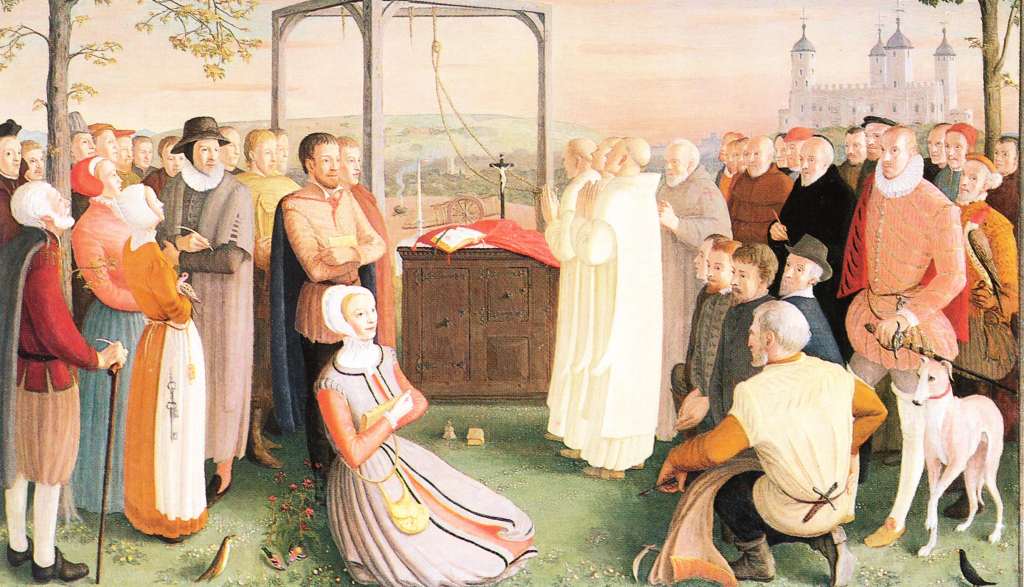

Forty Martyrs of England and Wales, by Daphne Pollen, commissioned by the General Postulation of the Society of Jesus

Review: Pedro de Ribadeneyra’s “Ecclesiastical History of the Schism of the Kingdom of England”: A Spanish Jesuit’s History of the English Reformation, ed. and trans. Spencer J. Weinreich, June 2018

Moreana, Volume 55 (Number 209) Issue 1, Page 113-119, ISSN 0047-8105 Available Online May 2018

To download the full text, click here: https://www.euppublishing.com/doi/full/10.3366/more.2018.0034

Full Text

This first English translation of the Historia ecclesiastica del scisma del reyno de Inglaterra 1 represents an important contribution to studies of the Reformation in England. The Historia was originally published early in 1588 and offered a Catholic view of the English Reformation by a Spanish Jesuit, which has been the account held by most people in Spain since then about the matter, at least until recent times. The Historia covered the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary, and Elizabeth I. It was through the Historia that much of the Catholic world, and specifically non-Latinate Spanish people, knew of the barbarities of Henry, of the Protestant reformation introduced during the childhood of King Edward, of the brief Catholic restoration under Mary, and the persecutions of Catholics under Elizabeth. It was again through the Historia that Spaniards over the centuries came to know the figures of Saints John Fisher and Thomas More. The Historia is certainly a part of Spanish culture. It played an important role in encouraging the Spanish Armada against Elizabeth, and this edition actually includes in Appendix 1 the “Exhortation to the Soldiers and Officers Who Embark Upon This Expedition to England,” which departed in August 1588. Perhaps less well known by the reader is that Henry sought and obtained from Cranmer a decree of nullity of his marriage with Anne because he declared he had had prior intercourse with her sister. The edition of 1588 ended with the “Imprisonment and death of Queen Mary of Scotland” as decreed by Elizabeth. It is worth quoting a letter from Fray Luis de Granada of August 13, 1588 (Appendix 3): “I read the entire book from cover to cover, and shed many tears at various places, most of all at the death of the queen of Scotland.” And he continues:

‘They shall see how the pretensions of ascending to the heights by artifice and human means, without the fear of God, end in spectacular falls. For that wretched Archbishop Wolsey, not content with the place to which the world had raised him from the dust of the earth, aspired to become pope.‘

Indeed, if the English schism was started by the lust of Henry, it was also, in the judgment of Ribadeneyra, due to the ambition of Wolsey.

After the defeat of the Armada, Ribadeneyra published in 1593 his second part, Segunda parte de la historia ecclesiastica del scisma de Inglaterra, which stood alone as an independent volume until, from 1595 onwards, it was published together with the first part. The content of the second part is quite different. It includes coverage mainly of the persecution of Catholics in England under Elizabeth; of priests ordained on the Continent for the English Mission and executed in England, treating in particular of the story of St Edmund Campion; of the establishment of the English seminaries in Douai, Rheims, Rome, Valladolid, and Seville; of Elizabeth’s proclamation against seminarians, priests, and Jesuits; and the list of the martyrs who departed the English colleges and seminaries at Rome and Rheims from 1577 to 1594. The volume includes also Ribadeneyra’s letter on the Causes of the Armada’s Failure (Appendix 2). While the Exhortation to the Armada was full of providentialism and optimism based on the belief that the Armada was fulfilling the will of God and therefore was bound to succeed, the letter calls for accepting the result, and for seeing it as an opportunity for the king “to humble himself beneath the Lord’s mighty hand,” but also as an incentive to solve some social evils that existed in Spain at the time:

‘Our Lord has chosen to try our faith, revive our hopes, enflame our prayers, reform our customs, purify our intentions, and cleanse them of the filth of our private interests and worldly security, which many sought in this enterprise—perhaps with greater zeal than the exaltation of our sacred faith and the good of the lost souls of the English.‘

Yet the author also expresses his conviction of God’s wish of success in further attempts: “For my part, I am certain that he does not wish to deny it to us, but rather to put it off for a short time, and in the meanwhile to do us many and greater and more important mercies, of which we have greater need.”

In addition to the first translation into English, Spencer J. Weinreich provides a 110-page Introduction in which he gives a biographical account of Pedro de Ribadeneyra and his influence on Spanish culture, as well as exploring the Historia’s many dimensions: the politics behind the text, the propaganda for the Armada, the different editions of the Historia, its relation with the Society of Jesus, and reception of the Historia. The extensive annotations anchor Ribadeneyra’s narrative in the historical record, reconstruct his sources, and provide up-to-date scholarship on the matter.

The publisher has taken the initiative of printing in a different color variations introduced in the several editions of the Historia. In the first part, pages 112–548 of Weinreich’s edition, while most of the text follows the edition of 1588 of the Historia, red additions come from the 1595 edition. The text of this first part follows mainly that of the second edition of De origine ac progressu schismatis anglicani, which was edited by Edward Rishton and Robert Persons and published in Rome in 1586, while a full chapter on Thomas More, in red in the English edition, was added in 1595 from the biography of Thomas Stapleton published in 1588. This first part of the Historia, however, is not just a translation into Spanish of previous texts because the Historia addresses a different public and includes evaluations and insights by Ribadeneyra. The text of the second part, pages 549–737, is mainly that of 1593, and the few modifications—marked in red in the English edition—were introduced in the 1595 and 1605 editions.

It is worth focusing here on some of the themes emphasized in the Introduction. For Ribadeneyra the Anglican schism and the English Mission were not just academic topics or even the fruit of his concern for his fellow Catholics. Ribadeneyra had joined the Society of Jesus in 1540, a few days before the order had received papal approval, and he was always very close to St. Ignatius, its founder, of whom he wrote a well-known and highly-praised biography. In 1553 Ribadeneyra was sent by St. Ignatius to the Low Countries to obtain permission for the establishment of the order there: “At the end of his life Ignatius was anxious about bringing the Society to England and had laid upon Fr Ribadeneyra the task of seeking for an opportunity of doing so.” Queen Mary (r. 1553–58) and Cardinal Pole had not granted permission for the establishment of the Jesuits in the kingdom. Ribadeneyra was able to go to England in November 1558, but a few days after his arrival Mary and Pole died, frustrating Ribadeneyra’s dream of fulfilling St. Ignatius’s final wishes. Thus, the history of the Catholics in England was very close to Ribadeneyra’s heart.

There is a point that might perhaps be missed by non-historian British and North American readers. We speak often of those Englishmen who during the reign of Elizabeth moved to the continent. For instance, Sander (c. 1530–81), Allen (1532–94), Stapleton (1535–98), Campion (1540–81), Persons (1546–1610), and Rishton (1550–85) had all studied at Oxford, left England between 1560 and 1573, and spent some time in Douai or Leuven. Even the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography writes of one of these, saying “he moved to France to study at the college of Douai.” That is not so. Douai and Ghent in the County of Flanders, and Leuven, Brussels, and Antwerp, in the Duchy of Brabant, were cities that had belonged to the Dukes of Burgundy from 1430, and thence in 1477 passed into Habsburg possession. The Emperor Charles, born in Ghent, became Duke of Burgundy in 1506, and king of Castile and Aragon in 1517. The Burgundian territory belonged to the Spanish branch of the House of Habsburg from 1522. France relinquished its claim on Flanders in 1528. Charles declared the Low Countries to be a unified entity in 1549, and Philip II was made Lord of the Netherlands from 1555. Therefore, the University of Douai established under the patronage of Philip II in 1559, the English College founded in 1561 (even though the English were expelled in 1578 and the college moved temporarily to Rheims in France only to return to Douai in 1593), the publication of the Opera Omnia Latina of Thomas More in 1565 in Leuven, and the biography of More by Stapleton printed in Douai in 1588, all took place under the Spanish king.

Ribadeneyra is full of praise of Thomas More, “a man of extraordinary genius, immense learning, and admirable virtue—and recognized as such by the entire kingdom” (Book 1, chap. 10), and keeps repeating his praise: “a man famous for learning and virtue, as has been said” (chap. 15); “an exceptional man, as has been said” (chap. 20). But he does not offer any new insights or information about More. He appears as a defender of Queen Catherine and of the validity of her marriage, a defender of orthodoxy against the writings of the heretics “as no ecclesiastic dared respond” to them (chap. 22). Ribadeneyra reports on More’s refusal to swear the Act of Succession, as well as on his imprisonment, trial, and martyrdom. The Historia mentions The Four Last Things, The Supplication of Souls, A Dialogue of Comfort against Tribulation, and De tristitia Christi, but no other works by More. Even though he is called a man of immense learning, his fame as a humanist is not mentioned, nor Utopia, known in the Low Countries and in all Europe. Stapleton reports extensively on More’s friendship with Erasmus, not without misgivings, but Erasmus’s name appears only twice in the Historia, first referring to the Edwardian Injunctions of 1547 which stipulated that the paraphrases of Erasmus upon the New Testament in English should be kept in all churches for all to read. Secondly, Ribadeneyra includes Erasmus of Rotterdam together with Henry VIII, Edward VI, Martin Luther, Peter Martyr, Wycliffe, Jan Hus, and Cranmer among the new confessors and martyrs claimed by the heretics in England.

The Historia is not actually a book about More but rather an ecclesiastical account of the schism. What is missing, however, is the use Cardinal Pole made of the figure of Thomas More as a means of fostering an English return to the Catholic faith, as has been pointed out by Eamon Duffy in his Fires of Faith. The student of More, nevertheless, learns in the History of the vision of More at the time. Ribadeneyra writes: “So exemplary was the life of Thomas More, and so illustrious his martyrdom, that I decided I ought to supplement what I said in the previous chapter ….” Two advantages may be derived from learning about More, Ribadeneyra says:

The first, that lawyers, judges, ministers, the favorites of princes, and the governors of the commonwealths will have a perfect model to imitate; the other, to teach us that the life of this exceptional man made him worthy to die shedding his unspotted blood for that Lord he had served … no wonder that King Henry strove by so many means to win him over … since the eyes of the entire kingdom were upon him.

There is another subtle thread. Seneca is cited only once in the Historia but Weinreich informs us of Ribadeneyra’s lifelong affinity for that stoic author—of Spanish birth—and adviser of Nero. A text from Seneca was copied in 1593 by Rowland Lockey on his version of the portrait of the “Family of Sir Thomas More.” This is not the place to unravel the origin of that quotation, but only to point out that reading the Historia one is made aware of the many events that had occurred between the martyrdom of More and the writing of that piece on the canvas.

Weinreich studies the various editions of the Historia. Apart from the incorporation of the Second Part described at the beginning of this review, it is especially interesting to notice the differences between the 1593 and the 1595 editions. In the 1593 edition Ribadeneyra was keen to give the text of the Royal Proclamation of October 18, 1591 that followed after the failure of the Armada. There, Elizabeth criticized the king of Spain for going to war, for having “arranged for a Milanese vassal of his to be elevated to the Roman pontificate, and prevailed upon him … to exhaust and waste the riches of the Church in raising soldiers,” for setting up seminaries and training priests who “extract a strict oath from those of our subjects with whom they engage to abandon the rightful submission they owe to us, to yield their obedience, property, and powers to the king of Spain, and to aid his army when it comes,” and so on. The inclusion of the offences attributed to the Pope and the king were considered to be scandalous for readers, and Ribadeneyra had to withdraw them in the 1595 edition where a descriptionof the proclamation is given rather than the full text, together with the measures decreed against the missionary priests and the fathers of the Society of Jesus, ending with a statement from Ribadeneyra saying

‘I wish to speak here only of what concerns our sacred religion, such as belongs to my history and what I have observed from the beginning, omitting all other matters … For this reason, I will not speak here of the edict’s absurdities and insanities against the pope and the Catholic King.‘

As have other scholars, Weinreich faces the question of whether Ribadeneyra might be considered a “modern historian,” one that gives his sources, tries to be impartial, and sticks to the truth. Among other things Weinreich points out that faith and the practice of religion are not to be considered foreign to a historical account, but they are part of the reality of man. In fact, “modern historians” are not always impartial but follow their own ideologies often, and try to be politically correct. Weinreich writes, “In the last pages of this introduction, then, I will endeavor to defend ‘the book’s intrinsic value,’ and suggest why it merits more serious study than mining it for a few isolated scraps of historical data.” He achieves his purpose.

With regard to grounding the Historia on sources as any historian is supposed to do, however, this reviewer finds the First Part—that is, that published in 1588—objectionable. Its source is almost exclusively Sander’s De origine ac progressu. From there Ribadeneyra takes the story that Thomas Boleyn told King Henry that Anne Boleyn was the king’s daughter. In the margin of the account in the first two editions of De origine ac progressu there is a note saying, “Haec narrantur a Guilelmo Rastallo judice in vita Thomae Mori” (Cologne, 1585, p. 15; Rome, 1586, p. 22). David Lewis, translator of De origine ac progressu into English (London: Burns and Oates, 1877), suggests that Sander based that affirmation on a now-lost Life of Sir Thomas More by William Rastell. The claim is quite implausible. The Rastell Fragments published by Elsie Vaughan Hitchcock for the Early English Text Society in 1932 (together with the Life by Harpsfield) start with Henry trying to obtain the divorce and consulting with Fisher and More, and deal with the case of the Nun of Kent, the refusal of the oath, imprisonment, trial, and execution. All this, and no more, is covered in Sander’s account of More. It does not seem likely that Sander had any more information from Rastell than what is contained in the extant Rastell Fragments. Stapleton based his Life on the accounts of John Clement and his wife Margaret, John Harris, Dorothy Coly, John Heywood, “and lastly William Rastell”; if Rastell had more information on the matter, Stapleton would have included it in his biography of More. Plainly, Ribadeneyra should have checked his sources before attributing the charge to Henry, and before accepting the attribution of the information to Rastell.

In spite of its evident bias, the Historia ecclesiastica del scisma del reyno de Inglaterra by Ribadeneyra gives a comprehensive view of the period—as ecclesiastical history, without dealing with economic or other social aspects—and is thus a more complete account in its kind that that found in either larger or briefer works. And the present English edition by Weinreich under the Brill imprint is very well produced, made for easy reading, and incorporating up-to-date scholarship.

*Note

1 Original spelling.

Leave a comment